Sillabari

Stories of Carpets and Graphemes

Every time, it is a small miracle that transforms a shapeless lump of clay into a work of art. Perhaps it is because the lump itself is a metaphor for radical insignificance, a primordial state of immobile matter, hyle, lacking any idea to convey. Perhaps it is because the transformation magically happens through fire, the firing, an archetypal act of civilization (without even resorting to Lévi-Strauss’s The Raw and the Cooked…). The fire that transforms, as in an alchemical process, the formless into an object, ob-iectum, something that stands before us and lets itself be questioned, questions us, because it bears signs. Perhaps it is because there is a work done by hand, fingers that imprint meaning on what is there, waiting. For all these reasons, seeing Gianna Albertin’s works unfold before me one after another was a profound emotion, as if, even before bending down to “read” the works, I was called to witness a kind of event. And the emotion lasted long, because the imprint the artist leaves on the clay is deep, able to consciously and intelligently subvert that artisanal destiny to which materials like wood, clay, and fabrics are often condemned by tradition.

The first works that appear before me are the splendid series of carpets. Ceramic carpets? It’s hard to imagine a more striking antithesis, since flexibility and softness hardly suit such a rigid and defined material. Yet thin layers of clay, skillfully worked and crossed by a dense network of marks, give us a weaving, bring to life a small miracle in which the clay animates itself with fringes, stretches out, and seems to have acquired an unheard-of flexibility. But another element is worth highlighting: the central seam thanks to which the carpet opens, literally, but at the same time unfolds in the sense that it recalls the idea of reading, of binding. It is important to emphasize this from the start because legibility is a trait that runs through the entire exhibition, not by chance gathered under the title Sillabari. Opening them, these earthen carpets reveal the wonder of a colorful world, made of spots and bright lines, but searching among the folds we already discover dense patterns of characters, secret discourses we are called to decode. On closer inspection, we are faced with a suggestive stratification of paradoxes: the carpet that lies on the ground becomes a carpet of earth, the carpet that should be spread out actually becomes vertical, constantly shifting the established order of relationships. There is even a rolled-up carpet, which will never open again, blocked as it is in its burnt earth rigidity, telling us of our exclusion, the impossibility for us humans to find a place to stay, a carpet in which to recognize ourselves. The carpet that brings us into the dimension of lightness and dream, of rest and gathering, has become an unattainable aspiration, unless we untie its hidden bonds and bring it back to life.

These symbolic readings might seem forced or exaggerated to some, were it not for some observations casually thrown out by the artist herself, who recalls how often the genesis of some works is inspired precisely by the urgencies and dramas of contemporaneity. This complex play of antitheses between rigidity and lightness, reality and dream, immobility and flight is a “material” reflection on the contradictions of our existence—political, social, but also individual—on the unresolved conflicts within each of us, on the irreconcilable contrast between desire, aspiration, and contingent reality. Consider, in this regard, the two magnificent works dedicated to the trees of life, archetypal sources of novelty so well rooted on a … flying carpet.

We are also involved in this game of displacement in the series I will call the parallelepipeds: boxes, in fact, minimalist and elementary structures that bear symbolic decorations, repeated and arcane forms that seem to contain in nuce profound revelations. But what strikes is the alternation of concave and convex, closed and open, with which the forms alternate, almost confronting us with an inside/outside that is our own questioning, our destiny of painfully oscillating between the self and the world, between a private and a public dimension in an irresolvable tension.

And who or what protects us from this lacerating dialectic? We need a shell that defines us, a shield that protects us, and providentially it is shields that come out of the kiln, large colored shields capable of providing us with armor to face the world, or, again in this play of suggestive reversals, capable of becoming bowls to gather us, to give us consistency and form. It is here, more than elsewhere, that we find Gianna Albertin’s hallmark, that kind of seal that makes her work recognizable: I refer to the graphemes that densely cover many surfaces of her works, like an archaic script never deciphered, containing secret and salvific formulas that are no longer revealed. One thinks of the first objects of our Western civilization, the Phaistos Disc or the Linear A tablets, still undeciphered: a tragic mockery, in the end, to be irreparably excluded from what were the first voices of our history, exiles from the secrets that might have saved us, deprived of the first axioms and forced to live with a perpetual sense of insignificance. This is what the mysterious characters engraved on Gianna Albertin’s terracottas tell and remind us: cadences of salvation, if only we could read them, memories of a lost wisdom whose mere proximity, though incomprehensible, is enough to console us.

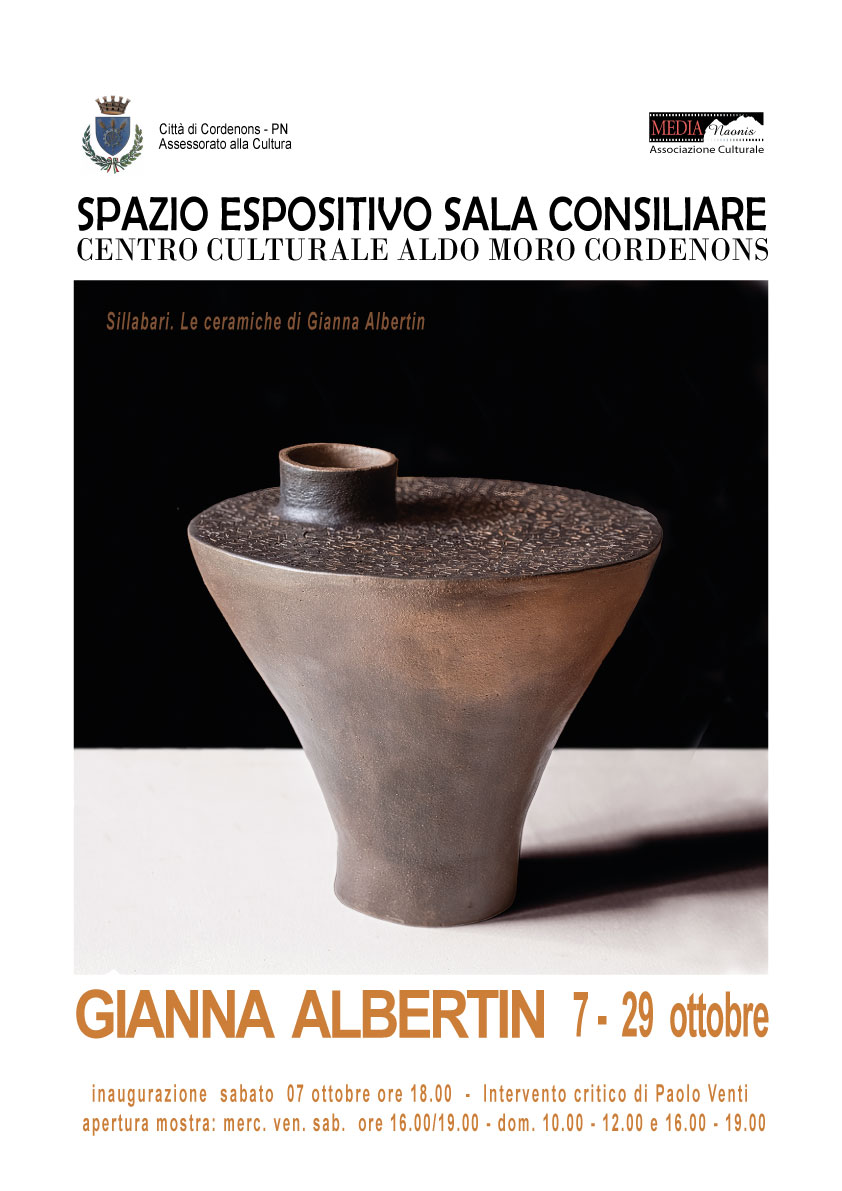

I leave for last, to complete the discourse, a series of other works in which all the possibilities of ceramics unfold for further suggestions of reading. I think of certain delightful little pictures in which the stratifications of earth and the effects of firing give us arcane, almost geological landscapes, lost places from when perhaps we did not yet exist, or of certain vases with improbable shapes in which a fullness of life seems to swell, on the verge of overflowing, of exploding. Or again, of certain sculptures with expanded and unexpected geometries that Gianna calls “the cycle of nature.” Perhaps to signify that if we can still find an answer to our anxieties and our exile, it is in the continuous miracle of reproduction, in the inexhaustible metamorphoses of the nature that surrounds us, capable, if only we let ourselves go, of capturing us again and inserting us back into our element, into the surprising flow of forms, always new and surprising, willing to let ourselves be colored by surprise as terracotta is unpredictably colored by a subtle current of oxygen or a slight temperature change.